Fique por dentro das novidades

Inscreva-se em nossa newsletter para receber atualizações sobre novas resoluções, dicas de estudo e informações que vão fazer a diferença na sua preparação!

Questão ativa

Já visualizadas

Não visualizadas

Resolução pendente

Questão anulada

Sem alternativas

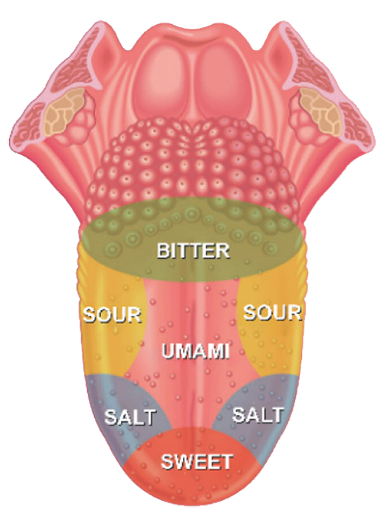

Think for a minute about the little bumps on your tongue. You probably saw a diagram of those taste bud arrangements once in a biology textbook — sweet sensors at the tip, salty on either side, sour behind them, bitter in the back.

But the idea that specific tastes are confined to certain areas of the tongue is a myth that “persists in the collective consciousness, despite decades of research debunking it”, according to a review published this month in The New England Journal of Medicine. Also wrong: the notion that taste is limited to the mouth.

The old diagram, which has been used in many textbooks over the years, originated in a study published by David Hanig, a German scientist, in 1901. But the scientist was not suggesting that various tastes are segregated on the tongue. He was actually measuring the sensitivity of different areas, said Paul Breslin, a researcher at Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. “What he found was that you could detect things at a lower concentration in one part relative to another,” Dr. Breslin said. The tip of the tongue, for example, is dense with sweet sensors but contains the others as well.

The map’s mistakes are easy to confirm. If you place a lemon wedge at the tip of your tongue, it will taste sour, and if you put a bit of honey toward the side, it will be sweet.

The perception of taste is a remarkably complex process, starting from that first encounter with the tongue. Taste cells have a variety of sensors that signal the brain when they encounter nutrients or toxins. For some tastes, tiny pores in cell membranes let taste chemicals in.

Such taste receptors aren’t limited to the tongue; they are also found in the gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas, fat cells, brain, muscle cells, thyroid and lungs. We don’t generally think of these organs as tasting anything, but they use the receptors to pick up the presence of various molecules and metabolize them, said Diego Bohórquez, a self-described gut-brain neuroscientist at Duke University. For example, when the gut notices sugar in food, it tells the brain to alert other organs to get ready for digestion.

New York Times. May 29, 2024. Adaptado.

Nós sentimos o sabor dos alimentos com o cérebro!

Esta afirmação à primeira vista nos parece estranha. No entanto, assim como ocorre em todos os sentidos do sistema sensorial, no caso do paladar, a percepção consciente do sabor só acontece quando sinais específicos chegam ao cérebro. Assinale a alternativa que apresenta corretamente a informação descrita neste processo.

Os componentes químicos dos alimentos interagem com proteínas receptoras nas células gustativas, e um potencial de ação é transmitido ao cérebro.

Os componentes químicos dos alimentos são convertidos em uma corrente elétrica que estimula o músculo da língua.

No processo de transdução sensorial do paladar, os componentes químicos dos alimentos são convertidos em um impulso hormonal que ativa as glândulas salivares.

Os componentes químicos dos alimentos ativam, diretamente, os neurônios responsáveis por transmitir os sinais gustativos ao cérebro.

A primeira etapa da transdução de sinal no paladar ocorre quando os receptores gustativos são ativados por hormônios digestivos.

Receptores químicos de neurônios interagem com moléculas específicas. Isso desencadeia o impulso nervoso, que é conduzido a uma área específica do cérebro, na qual a sensação de sabor é interpretada.

Inscreva-se em nossa newsletter para receber atualizações sobre novas resoluções, dicas de estudo e informações que vão fazer a diferença na sua preparação!